While cherry-picking--the act of suppressing evidence that doesn't support our own particular biases--is something to be avoided, berry-picking, on the other hand--carrying out our searches for information in a way that is not strictly linear and that incorporates cognitive questions, by allowing those searches to evolve and change in response to what we initially come across--is not only to be encouraged, but can be absolutely delightful in the unexpected directions it leads us.

This morning, berry-picking took me in a most unexpected direction. On the way to looking up something else, I came across this:

Risks of consuming fermented foods

Alaska has witnessed a steady increase of cases of botulism since 1985. It has more cases of botulism than any other state in the United States of America. This is caused by the traditional Eskimo practice of allowing animal products such as whole fish, fish heads, walrus, sea lion, and whale flippers, beaver tails, seal oil, birds, etc., to ferment for an extended period of time before being consumed. The risk is exacerbated when a plastic container is used for this purpose instead of the old-fashioned, traditional method, a grass-lined hole, as the botulinum bacteria thrive in the anaerobic conditions created by the air-tight enclosure in plastic.--Wikipedia, "Fermentation: Risks of consuming fermented foods accessed 3 October 2012

Slightly off-topic, but interesting (I think!), in a berry-picking way, since we care about calling people by the names they want to be called: Did you notice that the paragraph used the word "Eskimo", and did that perhaps seem a little strange to you, because you've heard that you shouldn't use the term "Eskimo" when you mean the Inuit people, since the word is derogatory or pejorative or insulting?

You're not wrong, if you remember hearing that--the word "Eskimo" probably does, historically, have connotations that are belitting and insulting, and Native American and First Nations people have spoken out explicitly and firmly against the use of the word.

At the same time, there is no good inclusive replacement term that includes the Yup'ik peoples of Alaska--if you just say "Inuit" instead of "Eskimo", that's fine if you mean only Inuit people and no one else.

But if you mean Inuit people together with Yup'ik people, then there really isn't a well-known acceptable term that means both. So often, you will see Alaskan Native American (more so) and Canadian and Greenlandic First Nations and Inuit people (less so, or maybe even not at all, per Lee Kalpin's comment following this post) compromising, and using the term in order to be inclusive, despite the connotations that go along with the word.

What's happening in Alaska?

Alaska has witnessed a steady increase of cases of botulism since 1985. It has more cases of botulism than any other state in the United States of America.--Wikipedia, "Fermentation: Risks of consuming fermented foods accessed 3 October 2012

Botulism is a condition that paralyzes people and animals who eat food contaminated with botulin toxin, or who have an open wound through which the bacteria that produce the toxin (Clostridium botulinum) can enter the body. C. botulinum is an obligate anaerobic bacterium, meaning that it is obliged to grow in an environment without air--oxygen is deadly to it.

VERY IMPORTANT WARNING

This is why you absolutely never, under any conditions at all, give honey to babies under 1 year old--they don't yet have the immunity to fight off the bacteria that produce the toxin.

After 1 year of age and older, people can fight off the actual C. botulinum bacteria themselves, so the bacteria can't gain a foothold in their systems to begin pumping out the toxin.

But if the neurotoxic poison produced by that bacteria has already contaminated the food somehow--as opposed to the bacteria themselves--then that toxin can produce botulism in anyone.

Facial paralysis which spreads through the body is a typical symptom of botulism; very bad cases can actually cause death by paralyzing the muscles needed to breathe.

The 14-year-old in these pictures from Wikipedia show the paralysis that's typical of severe botulism. Although he appears dead, he was actually fully conscious, yet unable to move. His eyelids were drooping and his eyes were paralyzed, and the pupils were fixed and dilated. We hope he made a full recovery--Wikipedia doesn't tell us how his story turned out--but even if he did, it would require a long, slow, difficult path to rehabilitation.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

"A 14-year-old with botulism. Note the bilateral total ophthalmoplegia [paralyzed eyes] with ptosis [drooping eyelids] in the left image and the dilated, fixed pupils in the right image. This child was fully conscious."

Source: http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/b/b4/Botulism1and2.JPG accessed 3 October 2012

From 1950 to 1997, 105 confirmed outbreaks of foodborne botulism involving 214 persons occurred in Alaska (there were no confirmed cases during 1947-1949)...All cases occurred in Alaska Natives. The average annual incidence among Alaska Natives increased from 3.5 cases/100,000 population during 1950-1954 to 10.7 cases/100,000 during 1995-1997 [in other words, right about 3 times as many cases as you'd expect, based on history].--State of Alaska Public Health Epidemiology Report: Botulism in Alaska--A Guide for Physicians and Health Care Providers, 1998 Update accessed 3 October 2012

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Source: State of Alaska Public Health Epidemiology Report: Botulism in Alaska--A Guide for Physicians and Health Care Providers, 1998 Update http://www.epi.hss.state.ak.us/pubs/botulism/fig_1.gif accessed 3 October 2012

They have a website where they promote cross-cultural understanding by presenting pictures and reports of daily life, festivals, and other events.

In a post, "The Best of the Whale", one of their writers, Bogdan, presents pictures from Ilisagvik Inupiaq Culture Camp, where elders and others share a meal of traditional foods.

Notice the blue plastic container, and the Ziploc plastic bags--we're going to get back to those in a moment.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Source: http://ecci-2012.s3.amazonaws.com/thumbs/20120814_ecc_grp_iic_awi_70_502ab33f88f97.JPG.poster.jpg accessed 3 October 2012

Bogdan describes the scene:

The most desirable food served at the blanket toss festival is fermented whale meat and blubber (mikiaq). Elders particularly like mikiaq, because it is easy to chew. To keep the audience interested and at the site, mikiaq is served last, after all the other food items have been distributed.

Mikiaq is

raw whale blubber that has been left to soak and ferment in the whale's blood.

Fermentation occurs when, under anaerobic conditions (reduced or no oxygen), you convert sugars (carbohydrates containing carbon [C], hydrogen [H], and oxygen [O] atoms as building blocks) like the kinds of glucose here:

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Source: http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/0/06/DL-Glucose.svg accessed 3 October 2012

into ethanol, the kind of alcohol in drinks such as beer, wine, and spirits, a process which rearranges those atoms into this arrangement:

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Source: http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/3/37/Ethanol-2D-flat.png accessed 3 October 2012

Greenlandic to English Dictionary

nuna iterssaliorpâ: digs a hole in the ground, p. 180 (Old orthography)

qasaerdlâq: a seal which has been put by whole and left to ferment, p. 211 (Old orthography)

Back in the old days, fermenting the mikiaq was accomplished by digging a hole in the ground, and leaving it there for as long as it took the process to occur naturally.

Nowadays, just like most of the rest of us reading this, circumpolar peoples have access to modern conveniences like the blue container and the Ziploc bags you saw in the photo from the festival.

Plastic bags, containers, and utensils, no matter how bad they are for the environment, have some convenient qualities that make them so widespread in food preparation. One of those properties is the ability to keep food fresh for longer periods of time.

It does this by sealing the food away from exposure to air that would cause it to decay faster. In other words, it promotes an anaerobic environment.

And that's where the connection to the increased cases of botulism lies.

This is caused by the traditional Eskimo practice of allowing animal products such as whole fish, fish heads, walrus, sea lion, and whale flippers, beaver tails, seal oil, birds, etc., to ferment for an extended period of time before being consumed. The risk is exacerbated when a plastic container is used for this purpose instead of the old-fashioned, traditional method, a grass-lined hole, as the botulinum bacteria thrive in the anaerobic conditions created by the air-tight enclosure in plastic.--Wikipedia, "Fermentation: Risks of consuming fermented foods accessed 3 October 2012

Fermentation in a grass-lined hole, while still an anaerobic process, is less efficient at keeping the oxygen out, since air will circulate in and out of the hole and between the blades of grass. The C. botulinum bacteria have to overcome the deadly oxygen in that air, if they are going to establish a strong enough foothold to produce enough neurotoxin to make the mikiaq dangerous to the people who eat it.

A plastic container, on the other hand, does a much better job of keeping out the oxygen. Less oxygen in the container means a more welcoming environment for C. botulinum, where they can start to churn out neurotoxin.

As plastics have come into wider and wider use in the general population, and as they have made their way to more remote areas, where the convenience appealed to people, they took the existing risk of botulism, and--by providing a better anaerobic environment--sent the cases of botulism much higher than had been the case when mikiaq used to be fermented in the traditional grass-lined hole.

What all this means is that--contrary to what you may have heard--evidence-based practice does not mean that you have to give up traditional practices just because they are traditional, and adopt modern practices just because they are modern.

It means that instead of a top-down simplistic rule-based approach (either "Old = Good! New = Bad!": the "Argument from antiquity" fallacy, or the other way around, "Old = Bad! New = Good!": the "Argument from modernity" fallacy), we take a bottom-up approach of examining the evidence itself, and then deriving more nuanced and accurate rules that we can turn around and apply. Which, in turn, means that everything, traditional and modern alike, gets examined to find out:

- what works in the way it claims to,

- what doesn't work in the way it claims to, and

- the mechanisms for why that is the case.

Once we better understand the answers to those questions, we can better decide which practices fit better into our client-centered model of service, and why they do so. This example was a perfect demonstration of how sometimes evidence supports the traditional practice as objectively better, as measured on the basis of outcomes (number of cases of botulism), than the modern practice.

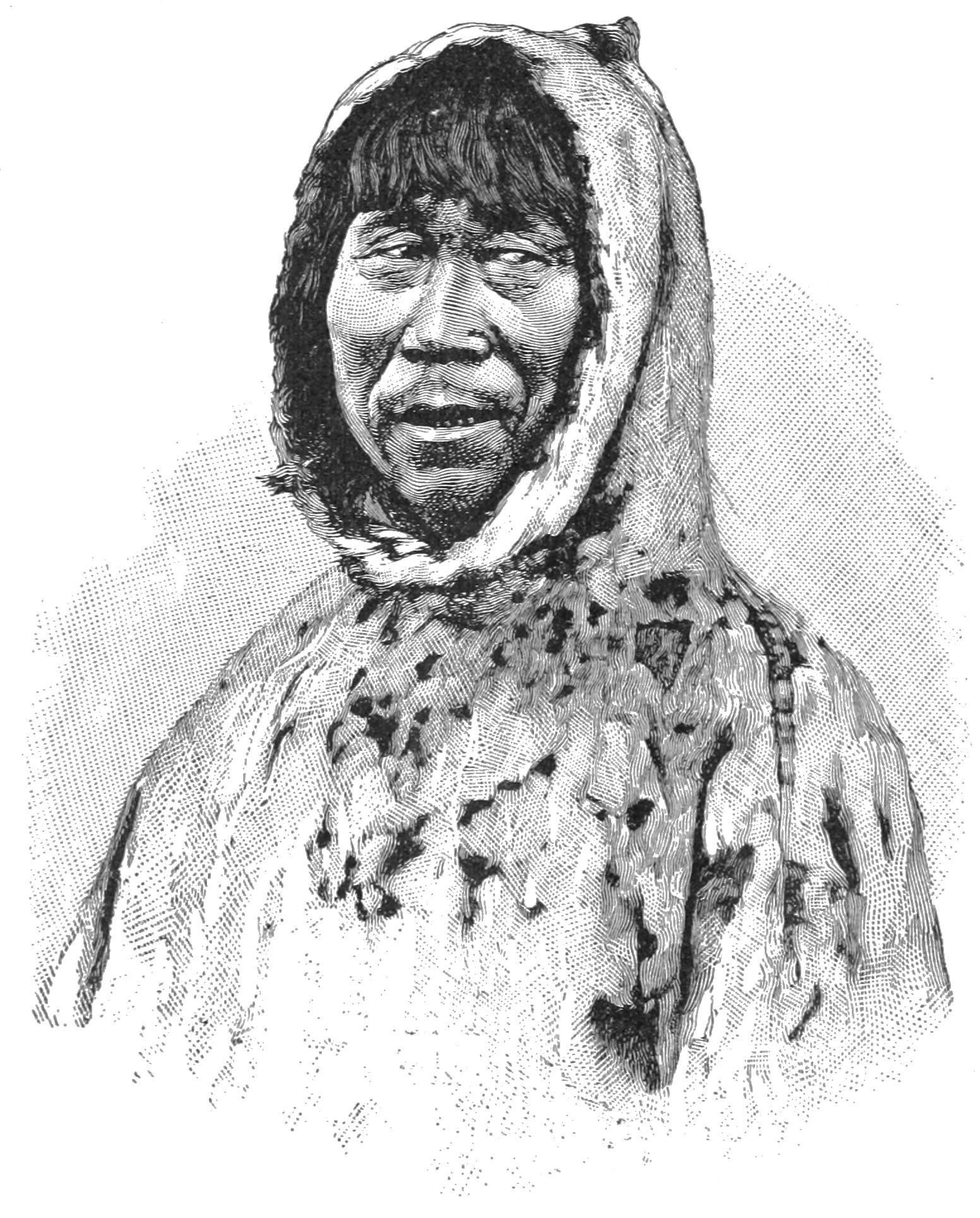

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Source: http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/e/e2/PSM_V37_D324_Greenland_eskimo.jpg accessed 3 October 2012